Introduction

Kissing bug disease and Chagas disease, also known as American Trypanosomiasis, enters the human body like a silent pandemic and lives unnoticed for years. It causes severe damage to the heart and the digestive system, two of the most vital organs of the human body, the first symptom of which can be an unexpected heart attack or stroke. The main cause of this disease is a protozoan parasite scientifically named

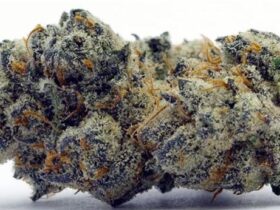

Trypanosoma cruzi. This parasite enters the human body through a blood-sucking insect called the

triatomine bug or “kissing bug”. These bugs usually bite sleeping people on their face or around their eyes at night and then defecate near the bite site. This strange behavior is what earned them the name “kissing bug.” While the name may sound harmless at first, the reason behind it and its fatal consequences create a powerful paradox in the human mind, which further highlights the gravity of this disease.

Historical Context

The history of the discovery of Chagas disease is both fascinating and tragic. In 1909, the Brazilian physician Carlos Ribeiro Justiniano das Chagas was the first to fully identify the disease, its parasite, its vector, and its effects on humans. His discovery was an unprecedented event in the history of medicine, where a single researcher uncovered a new disease, its vector, and its parasite all at once.

Carlos Chagas was working in a remote area of Brazil to prevent malaria among railroad construction workers. There, he noticed that people living in thatched huts were being bitten by a type of blood-sucking bug, which locals called “barbeiros” or “barbers”. He studied these bugs and identified the presence of the

T. cruzi parasite in their guts. Subsequently, he found this parasite in a two-year-old child named Berenice from the same region and identified Chagas disease as the first confirmed human infection.

Although Chagas’s discovery was a huge scientific success, it took almost two decades for his work to be recognized. Due to the envy of his colleagues, misconceptions, and the political stagnation of the time, his research was ignored for nearly twenty years. This led to a serious delay in awareness and preventive research regarding the disease’s spread. This is one of the main reasons why the disease became known as a ‘neglected tropical disease’. This historical event is not just a story of scientific success but also proves that the progress of science and research can be influenced by social and political realities. The fact that Chagas disease was limited to poor and marginalized communities is why it failed to attract the attention of public health systems for a long time. This continuous neglect continues to keep the disease a serious public health problem in many parts of the world today.

Disease Stages and Symptoms: When the Body Doesn’t Speak

Chagas disease infection is divided into two main stages in the human body: the acute phase and the chronic phase. The most dangerous aspect of this disease is its silent nature, which often makes early diagnosis impossible.

Acute Phase

The first few weeks or months of infection are called the acute phase. During this time, the number of parasites in the blood is relatively high. However, in most cases, the symptoms of this phase are mild or non-existent, making it difficult to diagnose. If any symptoms do appear, they are often similar to those of other common illnesses, such as fever, fatigue, body aches, headache, rash, vomiting, and diarrhea.

However, some distinct symptoms may also appear during this phase:

- Chagoma (Chagoma): This is an inflammatory, swollen lesion that typically forms at the site of the bug bite. It may look like a boil or a rash and is often mistaken for a bug bite or a common allergic reaction.

- Romaña’s sign (Roman~a′s sign): This symptom is very characteristic. If the bug’s feces are accidentally rubbed into the eye or the parasite enters the body through the eye, one eyelid swells up. This symptom can be very important for the early diagnosis of the disease.

Chronic Phase

After the acute phase, the disease enters the chronic phase, which can last for decades or even a lifetime. During this time, the number of parasites in the blood decreases, and they primarily hide in the tissues of the heart, digestive system, and nervous system. Approximately 70% of infected individuals do not experience any symptoms during this chronic phase. This asymptomatic state is what turns the disease into a “silent killer.”

However, about 20-30% of infected individuals eventually suffer from serious health complications. These complications include:

- Heart-related problems: This is the most serious consequence of Chagas disease. Events such as an enlarged heart (Dilated cardiomyopathy), irregular heartbeat (arrhythmias), heart failure, and sudden death can occur. In many cases, the first sign of the disease can be a life-threatening event, such as a heart attack or a stroke.

- Digestive system problems: Infection with this parasite can cause the esophagus and colon to swell abnormally, known as megaesophagus and megacolon, respectively. This causes severe difficulty in swallowing food and in bowel movements.

- Neurological problems: In some patients, chronic infection can also cause nervous system disorders.

The dual nature of this disease, where the initial phase is asymptomatic and the chronic phase is dormant, establishes it as a complex health problem. In many cases, by the time a patient seeks treatment, the disease has already caused irreversible damage to their internal organs.

The differences between the two stages of Chagas disease are highlighted in the table below, which will help readers understand the complex nature of this disease:

| Stage | Duration | Common Symptoms | Parasite Presence | Treatment Goal |

| Acute Phase | Weeks to months | Fever, fatigue, body aches, swelling, rash, Romaña’s sign | High levels circulating in the blood | To eliminate the parasite |

| Chronic Phase | Decades to a lifetime | Often asymptomatic; in severe cases: heart problems (cardiomyopathy), digestive problems (megacolon), neurological complications | Hides in the muscles of the heart and digestive system | To manage symptoms, slow down disease progression |

Export to Sheets

Disease Transmission: Dangers from an Unfamiliar Path

The transmission methods of Chagas disease are multifaceted and not limited to a single vector, which makes the disease even more complex.

Vector-borne Transmission

The main and most common method of Chagas disease transmission is through the kissing bug or triatomine bug. When infected bugs feed on the blood of a human or a wild animal, the

T. cruzi parasite in their body enters the bloodstream. After feeding, the bug often defecates near the bite site. If a person accidentally rubs this feces into the bite wound, their eyes, or the mucous membranes of their mouth, the parasite easily enters the body and causes infection.

It is a very important fact that not all kissing bugs carry the parasite. These bugs are often born healthy and become infected with the parasite after biting an infected animal or person. This information helps to dispel unnecessary fear and encourages a focus on the real risks.

Other Transmission Methods

Besides vector-borne transmission, Chagas disease can also spread through several other rare means:

- Congenital transmission: The disease can be transmitted from an infected pregnant mother to her baby.

- Blood transfusions and organ transplants: If blood or an organ from an infected person is transplanted into a healthy person, there is a possibility of disease spread. This is why screening for Chagas disease before blood donation and organ transplantation has been made mandatory in many countries worldwide.

- Food and beverages: In very rare cases, if any food or drink is contaminated by the feces of an infected bug, consumption of it can also lead to infection.

- Laboratory accidents: Infection can occur from unintentional contact with the parasite during research.

The disease does not spread through general personal contact. That is, it does not spread through sneezing, coughing, casual skin contact, kissing, hugging, or sexual intercourse. This kind of information plays a crucial role in dispelling common misconceptions about the disease and increasing public awareness.

Chagas Disease Worldwide: A Neglected Health Problem

Although Chagas disease has historically been viewed as a problem of Latin America, its global picture is rapidly changing. This disease is no longer just a regional problem; it is a global public health concern.

The Latin American Context

Chagas disease is a major health problem in the rural areas of 21 Latin American countries. According to World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, approximately 6-7 million people in this region are infected with

T. cruzi, and over 10,000 people die each year. The spread of this disease is closely linked to poverty and poor housing conditions. Huts made of mud, straw, or clay create a suitable environment for triatomine bugs to breed, which greatly increases the risk of infection.

An important observation here is the vicious cycle that exists between the disease and poverty. Poor housing conditions increase the risk of the disease, and the disease leads to a decrease in work capacity, which pushes families further into poverty. For this reason, the disease is described as a “poverty-related” and “poverty-promoting” disease.

Spread to Other Continents: A New Challenge

Due to widespread human migration in recent decades, Chagas disease has spread to non-endemic areas like the United States (US), Europe (especially Spain), Australia, and Japan. Currently, approximately 300,000 people are infected with the disease in the US, most of whom are immigrants from Latin America. This spread has posed new challenges to the public health systems of non-endemic countries, as there is a lack of awareness about this disease among doctors and healthcare workers there.

United States: At the Center of a Regional Debate

Historically, the United States has been considered a non-endemic country for Chagas disease, but growing evidence is challenging this notion. Currently, triatomine bugs have been found in 32 states, and locally acquired human infections have been confirmed in California, Texas, Arizona, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee.

- Texas: This state has been identified as a hotspot. Between 2013 and 2023, there were over 50 locally acquired human infections. The infection rate in dogs in Texas has been found to be between 10% and 50%, which proves that pets are serving as a major reservoir for the parasite.

- California: Especially in the Los Angeles and San Diego desert areas, wild animals (such as opossums, raccoons, rats) act as carriers of this parasite.

The identification of Chagas as non-endemic in the US public health system has created a serious problem. This misconception is the main reason for the under-diagnosis and under-reporting of the disease. As a result, doctors and healthcare workers fail to grasp the seriousness of the disease, and patients receive treatment late, by which time the disease has reached the chronic phase. This highlights a serious systemic failure, which emphasizes the need for public health policies and awareness programs.

The global statistics and spread of Chagas disease are presented in the table below:

| Region | Estimated Number of Infected People | Annual Deaths | Main Risk Factors |

| Latin America | 6-7 Million | ~10,000 | Rural poverty, poor housing conditions |

| United States | ~300,000 | Data not available | Migration, local transmission through wildlife |

| Europe | ~50,000 | Data not available | Migration, blood transfusion/congenital transmission |

Export to Sheets

Diagnosis and Treatment Pathway

Treatment for Chagas disease is effective only when it is diagnosed quickly. But the path to diagnosis is quite difficult due to various obstacles.

Why Diagnosis is Difficult

The biggest obstacles to diagnosis are:

- In most cases, the early stage of the disease is asymptomatic or has mild symptoms.

- Lack of awareness about Chagas disease among doctors and the general public.

- The initial symptoms (e.g., fever, fatigue) are similar to those of other common illnesses, which can lead to misdiagnosis.

Diagnosis Methods

A correct diagnosis of Chagas disease is only possible by a healthcare provider who will consider the patient’s travel history and symptoms. The disease is then confirmed through various laboratory tests:

- Acute phase: During this phase, the number of parasites in the blood is high. Therefore, the parasite can be directly identified by examining a blood sample under a microscope.

- Chronic phase: In this phase, the number of parasites in the blood is low. Therefore, advanced methods like

- serological tests (e.g., ELISA) to detect parasite antibodies or Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) to detect parasite DNA are used.

Treatment Options

Two main antiparasitic drugs are used for the treatment of Chagas disease: Benznidazole and Nifurtimox.

- Efficacy: These drugs are highly effective in the acute phase of the disease and can completely eliminate the parasite in 90-100% of cases. These drugs are also effective in cases of congenital transmission. However, the longer the duration of the infection, the lower the efficacy of the drugs. Although it is difficult to eliminate the parasite in the chronic phase, these drugs can help slow the progression of the disease and reduce complications.

- Symptomatic treatment: If severe complications of the heart or digestive system appear in chronic Chagas disease, symptomatic treatment is provided for their management. This may include medication, pacemakers, surgery, or even a heart transplant.

- Challenges of treatment: Although effective drugs are available, they are not always accessible and can have side effects. Side effects include headache, fatigue, stomach pain, and skin reactions. Due to these side effects, many patients stop their treatment midway. This highlights both the limitations of the public health system and the personal difficulties for patients in getting treatment.

Prevention is the Best Way: Save Yourself and Your Loved Ones

Since there is no vaccine for Chagas disease, the most effective way to fight it is to prevent infection. Preventive strategies are important at both the individual and community levels.

Housing and Environmental Protection

- Home protection: Triatomine bugs can hide in cracks in the house, gaps in doors and windows, and holes in walls. Therefore, it is essential to seal these cracks and use secure screens on windows and doors.

- Cleanliness: Brush, woodpiles, rock piles, and other debris around the house should be removed, as bugs can nest in them.

- Bug control: Using insecticides to control bugs and sleeping under a bed net can reduce the risk of infection. Unnecessary outdoor lights should be kept to a minimum at night, as bugs are attracted to light.

Public Health Initiatives

- Screening programs: Screening for Chagas disease before blood donation and organ transplantation is a very important preventive measure. Screening programs should also be implemented for pregnant women to prevent congenital transmission.

- Awareness: It is very important to educate at-risk populations about the symptoms and transmission methods of the disease. They should be made aware that they need to consult a doctor quickly if symptoms appear.

To prevent the spread of Chagas disease, we cannot focus solely on human health. Research has shown that wild animals (such as raccoons, opossums) and pets (such as dogs) act as a major reservoir for this parasite. This means that to control this disease, the health of humans, animals, and the environment must be considered together. This highlights the need for a coordinated

‘One Health’ approach, which looks not just at human health but at the entire ecosystem.

Living with Chagas Disease: The Experience of Patients

To understand the human side of the disease, it is very important to listen to the personal experiences of some of those affected. The severity of the disease cannot be fully understood with statistics or data, but people’s stories bring that severity to life.

Miguel’s Story

Miguel’s Story: Miguel, a 38-year-old man living in Los Angeles, never smoked and had normal blood pressure. But he started to feel his heart beating abnormally. At first, he dismissed it as fatigue or a minor issue. Later, his feet and ankles began to swell, and he couldn’t sleep lying down due to shortness of breath. A year later, he was diagnosed and eventually advised to undergo a heart transplant. His story highlights the silent and deceptive nature of the disease.

Juan Bautista’s Story

Juan Bautista’s Story: Juan Bautista, a retired police officer from Colombia, was infected with Chagas disease without any symptoms. One day, after a sudden stroke, he was taken to the hospital, where Chagas disease was diagnosed as the cause of his chronic heart condition. His quote expresses the profound silence of this disease in the most powerful way: “If not for the heart attack, I would not have even known that Chagas disease exists”. He now lives with a pacemaker, and about 35% of his heart is damaged.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Here are the answers to some common questions about Chagas disease that will help you clarify your understanding of this complex disease.

Is Chagas disease contagious?

No, Chagas disease does not spread through general personal contact. It is not transmitted through sneezing, coughing, shaking hands, hugging, or sexual intercourse.

Do all kissing bugs transmit the disease?

No, not all kissing bugs spread this disease. Only some species of bugs carry the parasite, and even within those species, not all individual bugs are infected. The bugs are born healthy and become infected with the parasite after feeding on the blood of an infected animal or person.

Is Chagas disease curable?

Yes, Chagas disease is completely curable in its acute phase. If the disease is caught in the early stages and antiparasitic drugs (such as Benznidazole and Nifurtimox) are used, it can be almost completely cured. However, it is difficult to eliminate the parasite in the

chronic phase, and mainly symptomatic treatment is given then.

Should pregnant women receive treatment?

Pregnant women should avoid treatment during pregnancy. However, it is important to receive treatment after childbirth or before pregnancy, as infection can be transmitted from an infected mother to a newborn.

What should I do if I see a kissing bug?

If you see a kissing bug, never touch it with your bare hands. You can catch the bug using gloves or a plastic bag or a hard container and submit it to a local health center or pest control authority for testing.

What can be the side effects of treatment?

The main drugs used for the treatment of Chagas disease can have side effects. Common side effects include headache, fatigue, stomach pain, and skin reactions.

Conclusion

Chagas disease is a serious and neglected public health problem that is not just limited to Latin America but has now spread to other parts of the world due to global migration. The silent and deceptive nature of this disease has given it the name “silent killer,” which makes early diagnosis difficult and can cause severe heart and digestive system complications in the chronic phase.

However, the good news is that this disease is completely preventable and curable in its acute phase. Increasing public awareness, improving housing conditions, and implementing screening programs for blood donation and organ transplantation can play a significant role in preventing the spread of this disease. The necessity of a coordinated “One Health” approach in the fight against Chagas disease is undeniable, as it connects the health of humans, animals, and the environment.

The stories of thousands of affected people like Miguel and Juan Bautista remind us that Chagas disease is not just a medical problem; it is a human crisis. To tackle this crisis, we all must unite—doctors, public health workers, governments, and the general public—so that this silent killer can no longer take any more lives.

Hi, I’m M Saif, a digital marketer with a strong focus on SEO and content writing. I help businesses improve their online visibility, drive organic traffic, and create engaging content that converts. With a results-driven approach, I work on strategies that not only boost rankings but also deliver real value to audiences.

Leave a Reply